History of the Fort

The Need For Coastal Defense

The danger of naval attack along the North Carolina coast seems remote now, but during the 18th and 19th centuries the region around Beaufort was highly vulnerable to attack. Blackbeard and other pirates passed through Beaufort Inlet at will, while successive wars with Spain, France and Great Britian during the Colonial Period provided a constant threat of coastal raids by enemy warships. Indeed, Beaufort was captured and plundered by the Spanish in 1747, and again by the British in 1782.

North Carolina leaders recognized the need for coastal defenses to prevent future attacks and began efforts to construct forts. The eastern point of Bogue Banks was determined to be the best location from which a fort might guard the entrance to Beaufort Inlet. In 1756 construction began there on a small fascine fort known as Fort Dobbs. Fort Dobbs was never finished, and the inlet remained undefended during the American Revolution.

Early in the 1800s, continued strained relations with Great Britian caused the United States government to build a national defense chain of forts for protection. As a part of this defense, a small masonry fort named Fort Hampton, after a North Carolina Revolutionary War hero, was built to guard Beaufort Inlet during 1808-09. This fort guarded the inlet during the subsequent War of 1812, but was abandoned after the end of the war. Shore erosion and a hurricane in 1825 were responsible for sweeping Fort Hampton into Beaufort Inlet by 1825.

The War of 1812 demonstrated the weakness of existing coastal defenses and prompted the United States government into beginning construction on an improved chain of coastal fortifications for national defense. This ambitious undertaking involved the construction of thirty-eight new, permanent coastal forts known as the Third System. The forts were built between 1817 and 1865. Fort Macon was a part of this system. Fort Macon guarded Beaufort Inlet and Beaufort Harbor, North Carolina’s only major deep-water ocean port.

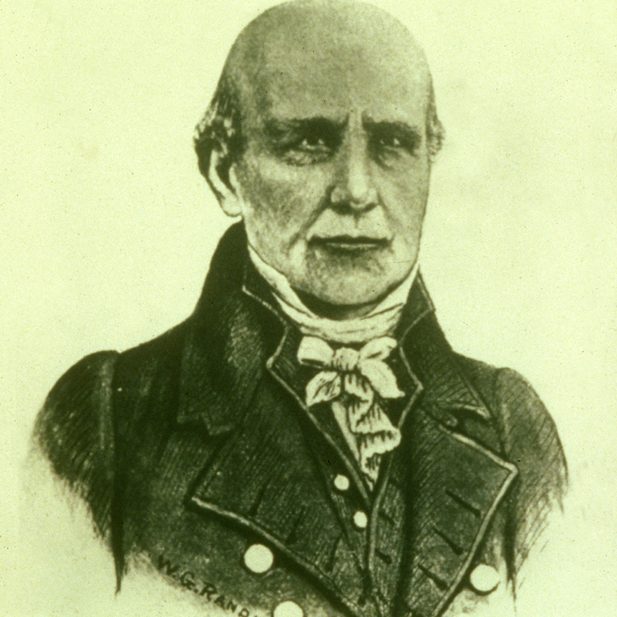

Fort Macon was designed by Brig. Gen. Simon Bernard and built by the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers. It was named after North Carolina’s eminent statesman of the period, Nathaniel Macon. Construction began in 1826 and lasted for eight years. The fort was completed in December, 1834, and was improved with further modifications during 1841-46. Total cost of the fort was $463,790. As a result of congressional economizing, the fort was actively garrisoned only from 1834-1836, 1842-1844 and 1848-1849. Often, an ordnance sergeant acting as a caretaker was the only person stationed by the Army at the fort.

The American Civil War

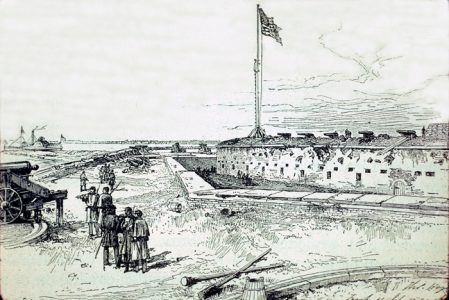

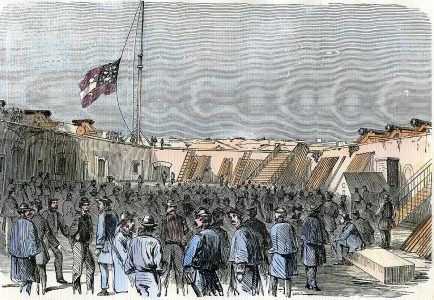

The Civil War began on April 12, 1861, and only two days elapsed before local North Carolina militia forces from Beaufort arrived to seize the fort for the state of North Carolina and the Confederacy. North Carolina Confederate forces occupied the fort for a year, preparing it for battle and arming it with 54 heavy cannons.

Early in 1862, Union forces commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside swept through eastern North Carolina, and part of Burnside’s command under Brig. Gen. John G. Parke was sent to capture Fort Macon. Parke’s men captured Morehead City and Beaufort without resistance, then landed on Bogue Banks during March and April to operate against Fort Macon.

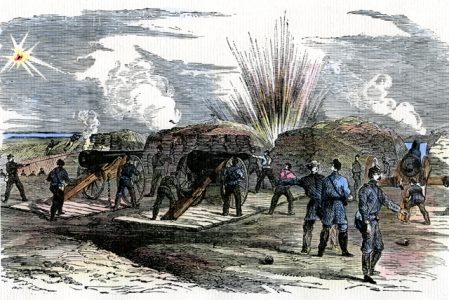

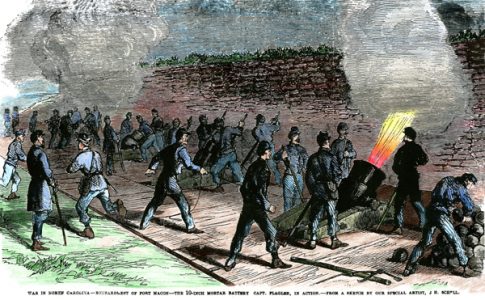

Col. Moses J. White and 400 North Carolina Confederates in the fort refused to surrender even though the fort was hopelessly surrounded. On April 25, 1862, Parke’s Union forces bombarded the fort with heavy siege guns for 11 hours, aided by the fire of four Union navy gunboats in the ocean offshore and by floating batteries in the sound to the east. While the fort easily repulsed the Union gunboat attack, the Union land batteries, utilizing new rifled cannons, hit the fort 560 times. There was such extensive damage that Col. White was forced to surrender the following morning, April 26. The fort’s Confederate garrison was then paroled as prisoners of war. This battle was the second time in history that rifled cannons had been used against a fort and demonstrated the obsolescence of fortifications such as Fort Macon as a way of defense.

The Union army held Fort Macon for the remainder of the war, while Beaufort Harbor served as an important coaling and repair station for the Union navy.

During the Reconstruction Era, the U.S. Army actively occupied Fort Macon until 1877. For about 11 years during this era, since there were no state or federal penitentiaries in the military district of North and South Carolina, Fort Macon was used as a civil and military prison, until 1876.

The Second State Park

Fort Macon was deactivated after 1877 only to be regarrisoned by state troops once again during the summer of 1898 for the Spanish-American War. Finally, in 1903, the U.S.Army completely abandoned the fort. The fort was not even used during World War I and in 1923 it was offered for sale as surplus military property. However, at the bidding of North Carolina leaders, a Congressional Act on June 4, 1924, gave the fort and surrounding reservation to the state of North Carolina to be used as a public park. Fort Macon and the surrounding property was the second area acquired by the state for the purpose of establishing a state parks system.

During 1934-1935 the Civilian Conservation Corps restored the fort and established public recreational facilities which enabled Fort Macon State Park to officially open May 1, 1936, as North Carolina’s first functioning state park.

At the outbreak of World War II, the U.S.Army leased the park from the state and actively manned the fort with Coast Artillery troops once again to protect a number of important nearby facilities. The fort was occupied from December, 1941, to November, 1944. On October 1, 1946, the Army returned the fort and the park to the state.

Today, Fort Macon is one of North Carolina’s most visited state parks, receiving more than a million visitors a year.

Outline of Fort Macon’s History

I. Purpose of Coast Defense at Beaufort Inlet

Defend the Harbor against hostile warships and sea attack.

Defense against the Spanish (when we were still an English colony); defense against the English (American Revolution and War of 1812); and defense against pirates who operated in North Carolina sounds.

Beaufort was captured and pillaged by the Spanish (1747), and captured by the English (1782)

(see article: Blackbeard’s visit to Beaufort Inlet)

II. Previous Forts

Fort Dobbs was begun in 1756 during French and Indian War, but the war ended and the fort was never completed.

In 1809, the Government built Fort Hampton, a circular brick masonry structure about 300 yards northeast of site of Fort Macon. Its guns protected the harbor through the War of 1812, but it was afterward abandoned. By 1825, storms and the shifting inlet had washed away some 200 yards of beach, including Fort Hampton. Lee noted in 1840 the site of the fort was denoted by a line of breakers offshore.

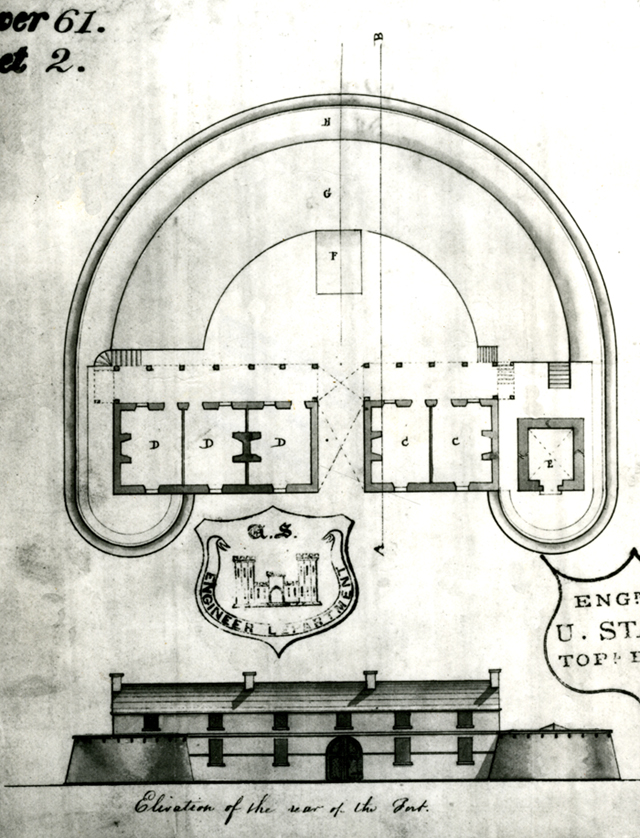

III. Building of Fort Macon

Fort Macon was part of a massive coastal defense program launched by President James Monroe to protect the coast without having to maintain a large navy.

Other forts on the coast (Sumter, Pulaski, Jackson, Jefferson, Morgan, Monroe, etc.) were part of the same program and could be considered sister forts of Fort Macon.

Fort Macon was named for Nathaniel Macon, very prominent North Carolina statesman of that period. Brig. General Simon Bernard was its architect.

Work started in 1826 and lasted 8 years to 1834. Chief Engineers who were responsible for constructing the fort were Lieutenant William Eliason, Captain John L. Smith and Lieutenant George Dutton, U.S. Army Engineers.

Cost of construction was $463,790. Some 9.2 million bricks were used.

IV. Physical Features of the Fort

Fort is of pentagon shape. One side guards mouth of inlet, two guard channel and back sounds, one looks over harbor, and one covers beach approaches.

Fort has outer line of defense (covertway) and an inner citadel. Separating the two is the “Ditch,” the bottom of which is near mean low tide level. It was sometimes filled with water which came up from the sound though a canal and passed under the outer wall by means of a culvert. The water was tidal.

The ditch was defended by four “Counterfire” rooms in the covertway which swept all avenues with rifle fire and small cannon firing anti-personnel ammunition. The purpose was to prevent enemy soldiers from overrunning the ditch and moat to penetrate into the main part of the fort.

The wall of the covertway (counterscarp wall) is 12 to 15 feet high. The outer wall of fort (scarp wall) is about 24 feet high. The wall inside fort overlooking parade ground is 17 feet high. The purple-gray stone used for stairways and coping on walls is Connecticut Freestone.

There are 26 casemates in fort (including sally port). The ceilings are arched to give added strength and dissipate concussion from shells exploding on terrepleins or from guns firing in battle. Rooms have fireplaces, two holes in ceiling for ventilation, and outer windows which are in reality rifle loopholes and gun ports.

Gutters in the walls caught rain water filtering through the sand from above and piped it to the four large cisterns located in the corners below the parade ground (they could hold 22,000 gallons). Because there was a seepage problem with salt water, the water was never used for drinking. Wells outside the fort provided drinking water.

Five sewers or drains carried water to a central drain in the center of the parade ground. This in turn was emptied by a pipe into the ditch under the bridge.

The fort had three magazines to store powder and ammunition, one located behind each of the three stairways. The stairways provided added protection against shellfire. Bathroom facilities were outside the fort. The fort “sink” was located at the head of the marsh for the big business. Droppings were carried away by the tide. Hospital, stables, storage buildings and quarters for some of the officers and married personnel were also located in buildings outside the fort.

V. Pre-Civil War

The fort was first garrisoned in December, 1834, although no guns were given for its defense until a year afterward.

From this time until 1861, it was intermittently occupied by troops, engineer detachments making repairs and improvements, or ordnance sergeants acting as caretakers.

Robert E. Lee, a captain of Army Engineers, visited the fort in December, 1840, making a thorough inspection of it.

VI. Confederate Occupation

The fort was seized April 14, 1861, by a company of local troops acting without state orders. Only one man, ordnance sergeant William Alexander, was in the fort at the time.

The state quickly garrisoned the fort with more companies, making in all about 900 men. There were 40 men living in each room. Finally, the garrison was reduced and the living conditions improved.

The Confederates worked feverishly to prepare the fort for battle over the next few months. A total of 54 guns were mounted for its defense (consisting of 10- and 8-inch Columbiads, also rifled and smoothbore 32- and 24-pounders). These were the most guns the fort ever had.

Just before the Federal attack (March, 1862), the garrison was reduced to five artillery companies, all of which were from North Carolina, and two of which were from Carteret County. The fort commandant was Col. Moses J. White, of Mississippi. He was 27 years old, ranked number two in the West Point Class of 1858, and suffered from severe epilepsy.

Major General Ambrose Burnside led Federal forces through the northeastern sound region of the state in February, 1862, and finally entered the Neuse River to capture New Bern on March 14. A portion of one of his brigades, commanded by Brig. General John G. Parke, was then sent down from New Bern to capture Fort Macon. Burnside wanted to have Beaufort Harbor in his possession for the use of his own supply ships, as well as the ships of the Federal Navy.

Parke easily captured Morehead City and Beaufort on March 23 and 26, respectively, and then transferred his troops, supplies, and artillery over to Bogue Banks. Three demands to surrender were refused by the fort.

After several skirmishes with Confederate soldiers, Parke’s men succeeded in entrenching as close as 1400 yards from the fort, while three batteries of siege guns (two batteries of mortars and one of 30-pounder Parrott Rifle guns) were established 1280 to 1680 yards from the fort.

On April 25, 1862, the Federal batteries opened fire on the fort. The Confederates responded with at least 21 of their 54 guns which could bear on the Federal positions. Four vessels of the Federal blockading fleet joined in from the ocean, but the fort’s guns quickly drove them off. Two ships suffered damage.

Federal fire was missing the fort for most of the morning due to obscuring battle smoke. The turning point of the battle came when a Federal signal officer in Beaufort noticed this fact and signalled range correction to the batteries. After noon, every shot fired at the fort struck it or exploded over it. The fort had no mortars of its own and was unable to do much damage to the Federals in return.

By 4:30 p.m., two of the fort’s powder magazines were in danger of being hit and exploded by Federal shells. Rather than be blown up by their own gunpowder, the garrison had little choice but to surrender. Federal forces took possession of the fort on the following day.

The fort had been hit 560 times by artillery fire. Seventeen guns were knocked out or damaged. Seven Confederates were killed, eighteen wounded. One Federal killed, three wounded. Burnside allowed the garrison members to return home on parole until exchanged.

VII. Federal Occupation

Federal forces continued to occupy Fort Macon through the remainder of the war. Battle damage was repaired and the Federals made certain they installed mortars for defense, so they would not repeat the mistake of the Confederates.

For the 12 years after the war, Federal soldiers continued to occupy the fort. It was used in this period as a Federal prison since there were no such prison facilities in either North or South Carolina during the Reconstruction.

The prisoners were mostly Government prisoners with an occasional civil prisoner (such as a murderer or rapist) thrown in. The most prisoners confined here at one time was 120, and the west wing was used mainly for their quarters.

In 1876 the prisoners were transferred elsewhere and by April of 1877 all the garrison troops at the fort were withdrawn. Reconstruction was ending and Government troops were being removed from the South.

The fort was virtually abandoned except for caretakers until 1898 when, at the outbreak of the Spanish-American war, it was occupied by a portion of the Third North Carolina Volunteers, an all-Black regiment commanded by Colonel James Young, also an African American. (North Carolina was one of three states requiring this arrangement.)

VIII. Creating a State Park

After 1903 the fort was abandoned for years. Finally, in 1924, the state acquired it from the Federal Government with the intentions of making it into a state park.

The lack of funds and the usual bureaucracy kept any work from being done until about 1934. At that time the Civilian Conservation Corps, one of the government work programs spawned by the Great Depression, began to work on the fort to counteract the years of neglect and make it presentable to the public.

By the 1940s the park was serving the public, thanks to their massive efforts.

IX. World War II

When war began in December 1941, the fort was once again occupied by troops. The first battalion of the 244th Coast Artillery arrived on the 21st of December and was later replaced by battalions from the 54th, 2nd and 246th Coast Artillery Regiments. Troops were quartered in the fort and in barracks outside. Radio and communications rooms, map-plotting rooms, and so forth were housed in the fort. On the beach were four M1917A1 155 mm G.P.F. seacoast guns, later replaced by two 6-inch navy guns, mounted on concrete platforms.

Although the troops here saw no action, the submarine war known as the “Battle of the Atlantic” was ever present. A number of allied ships and one German submarine were sunk just off the coast from the fort.

Two American soldiers were injured in Casemate 2 when a cannon shot they had placed in the fireplace as an andiron exploded from the heat of the fire. These men were both Northerners, so the local newspapers thought it humorous that two more “Yankees” had been gotten by a Confederate cannon ball some 80 years after the battle.

X. Recent History

After World War II, the fort again became a state park. Since that time, the fort has been restored by the State.

Fort Macon State Park is the most visited park in the state, with over one million visitors passing through here each year.

Fort Macon Bibliography

U.S. War Department, War of Rebellion, A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 Volumes in 128 Parts (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901). Volume IX, pages 270-294. The actual battle reports of the commanders involved in the Siege of Fort Macon are reprinted here.

U.S. Navy Department, The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of Rebellion, 30 Volumes (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1894-1927). Volume VII, pages 277-83. The battle reports of U.S. Naval vessels involved in the Siege of Fort Macon.

Walter Clark (ed.), The Histories of Several Regiments and Battalions From North Carolina in the Great War; Written by Members of the Respective Commands, 5 Volumes (Raleigh and Goldsboro: Nash Brothers, 1901). Volume I, pages 489- 491; 499-511. A good account of the Confederate occupation of Fort Macon, 1861- 62.

Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Being For the Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers, 4 Volumes, (New York: Thomas Yoseloff, Inc., 1956). Volume I, pages 652-54.

Paul Branch, The Siege of Fort Macon (Morehead City, NC: Herald Printing, 1982).

Available at Fort Macon Bookstore and at bookstores in Morehead City/Beaufort Area

Paul Branch, Fort Macon, A History (Charleston, SC: Nautical and Aviation Publishing Company of America, 1999) The definitive history of the Fort.(ISBN 1.877853-45-3)

Richard A. Sauers, A Succession of Honorable Victories, The Burnside Expedition in North Carolina, (Dayton: Morningside House, Inc., 1996), Pages 308-340.

John G. Barrett, The Civil War in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of N.C. Press, 1963), pages 10-11, 113-120.

Daniel H. Hill, Bethel to Sharpsburg, 2 Volumes (Raleigh: Edwards and Broughton Company, 1926). Volume I, pages 247-257.

Richard S. Barry, “Fort Macon: Its History,” North Carolina Historical Review,

Vol. XXVII (April, 1950), pages 163-77. A concise general history of Fort Macon.